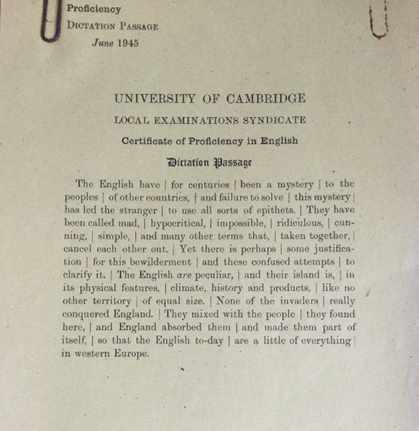

“The English have for centuries been a mystery to the peoples of other countries, and failure to solve this mystery has led the stranger to use all sorts of epithets.”

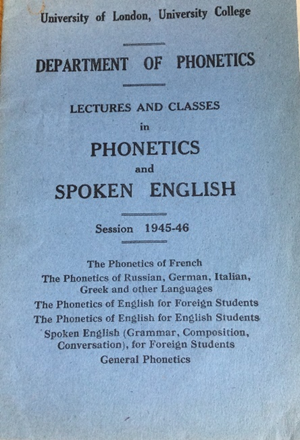

In June 1945 this sentence began the dictation passage in an exam paper for the Certificate in Proficiency in English. Around then my father, a student from Mosul in Iraq stranded in England by the war after arriving in London in the 1930s, was taking courses in Phonetics and Spoken English at University College (now UCL, University College London). Phonetics on a Wednesday afternoon with Mr J. T. Pring, the Grammar of Spoken English on a Tuesday afternoon with Mrs Hyacinth Davies.

I had no idea when I studied at UCL that my dad had ever been there. I found out recently through reading a collection of exam papers, timetables and regulations he gave me years ago. I assumed he’d expected me to find them useful for teaching English language and literature early in my academic career, so naturally I ignored them. But now I see them as comprising a rare miniature archive of data about provision for an influx of wartime refugees and (ex) service personnel. It’s also evidence of the educational approach taken under the great linguistics scholar and teacher Professor Daniel Jones (tagged the Real Professor Higgins by his biographer), and of older expectations of essential knowledge for foreigners about English culture, society, social class and language variety. Cambridge University set the exams in collaboration with the British Council. My dad’s practice papers from 1944 included translation from Arabic into English, and specific questions for people in the services. Candidates whose mother tongue was not English were required to translate both from and into English. In 1945 papers were provided in Arabic, Czech, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Norwegian, Persian, Polish, Russia, Serbo-Croat, Slovene and Spanish. Candidates could also give advance notice of requests for other languages.

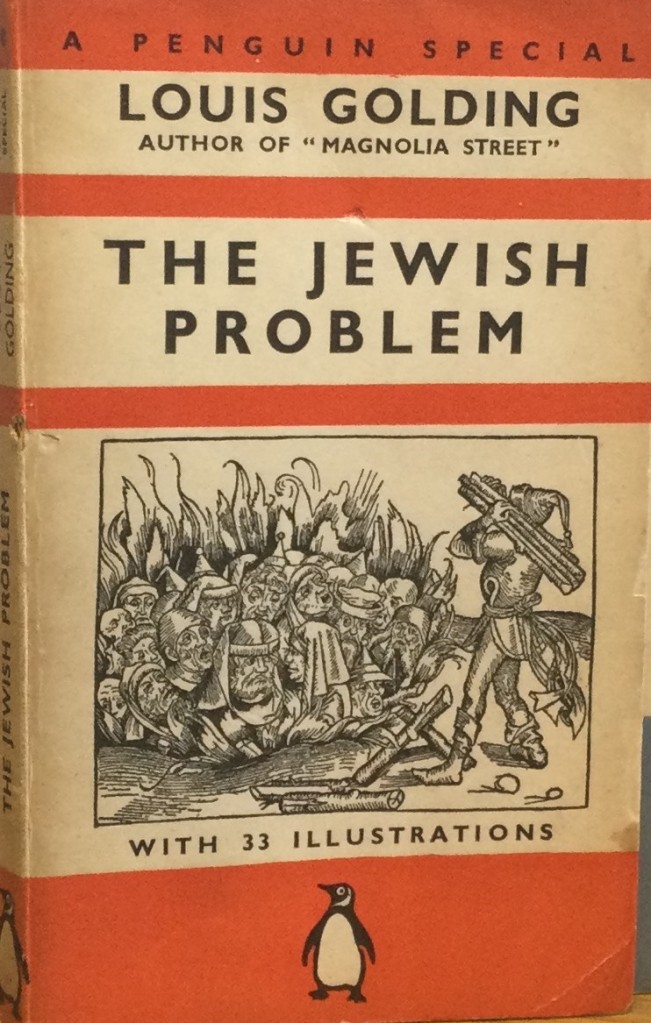

But there must have been so much more to try and understand about the English, for a young man coming to London in the 1930s when Mosley’s Blackshirts and other fascists were on the streets. How could he fathom English antisemitism? I know that must have been a question he tried to answer as I also have a collection of his books addressing that mystery. He owned Maurice Samuel’s The Great Hatred (1943), The Rev. A. Cohen’s pamphlet The Psychology of Antisemitism (1942), Louis Golding’s The Jewish Problem (1939, first published November 1938 and reprinted four times soon after), James Parkes’ An Enemy of the People: Antisemitism (1945), and Parkes’ The Jew and His Neighbour, his “study of the causes of antisemitism” (1938 edition, first published 1930), which my dad bought or was given in May 1941 according to his handwritten date on the flyleaf.

I can’t tell you what he made of them. But reading these older attempts to understand the mystery of English antisemitism brings back memories of experiencing it firsthand. It’s also depressing that those old examples and arguments are like so many still around today.

One of the authors, James Parkes, an ordained clergyman in the Church of England, made a lifelong study of antisemitism and helped found the Council of Christians and Jews. He wrote extensively about Christian antisemitism and saw that as a continuing problem. In his earlier book first published in 1930 Parkes took a long historical view and tried to account for antisemitism even-handedly as it were, by describing the effects of centuries of discrimination and oppression on Jewish lives, customs and characteristics. It’s meant to be a sympathetic narrative which urges readers to be more understanding, while at the same time it locates some “causes” in the targets of antisemitism. His attempt to explain why they are so disliked while saying it’s not entirely their fault does as much to confirm as to challenge the various stereotypes of Jew. So naturally Parkes’ conclusion was that it’s not just antisemites who need to address their behaviour. Parkes explained the origins of the Russian forgery Protocols of the Elders of Zion and the absurdity of its claims that Zionism is about world domination. But rather chillingly, writing in the 1930s he also discussed at length what he described as problematic about the existence of a large population of Jews in Poland.

His later book as you would expect – he wrote some parts in 1944 and others in 1945 – is a far more serious, analytical study of antisemitism as a political phenomenon in Europe and around the world. Instead of his previous focus on the history of the Jews, we get a focus on the historical, political, and economic contexts for local outbreaks and eventually the systematic spread of antisemitism. He dealt with the specifics of antisemitic campaigns and pogroms in numerous countries, how the infamous Protocols were spread, and the planned long-term nature of the Nazi machinery of propaganda. I would guess my father found this passage about the Arab world resonant, after he had been summoned home in 1941 by a pro-German regime in Iraq only to be torpedoed, shipwrecked and brought back to England.

“The Arab world…was selected for special care and attention. Prominent Nazi leaders took ‘holidays’ in Arab countries. Considerable numbers of Arab students were given scholarships to study in Germany, or at least free travel to visit Nazi conferences and meetings. While Mussolini poured out from his radio station at Bari anti-British ant-Jewish broadcasts, the Nazis, with great thoroughness, fished in the troubled waters of the Middle East, harping always on the two themes of the iniquity of the British and the iniquity of the Jews. There is nothing surprising in the Mufti finding a final home in Berlin, or in the rising in Iraq in 1941 [he’s referring here to the “farhud”, the attack on Jews in Baghdad after the pro-Nazi regime leaders fled, when hundreds were murdered and homes were looted]. Both were the result of years of careful German preparation.” (pp 62-63)

The other writers in my collection used the same kind of thematic structure as Parkes, going into the history of antisemitism, its manifestations, psychology and possible solutions. They agree that anti-Jewish sentiment (“ordinary dislike of Jews” in Maurice Samuel’s words) with its stereotyping and contempt should be distinguished from antisemitism with its crazed, fantastic imaginings about sinister Jewish power. Maurice Samuel even gives us as a list of cue words for anti-Jewishness and antisemitism to help us see the difference. What’s interesting now is that the first list of epithets – “kike” and so on – is obviously derisive racist abuse, but the second – “international plotter”, “enemy of civilisation” – you can well imagine being used by people even now who don’t see its racism.

Tony Kushner’s book The persistence of prejudice: Antisemitism in British society during the Second World War (1989) covers many more publications and analyses varieties of prejudice across a political spectrum, categorising them as left-wing, right-wing or liberal/centrist. Kushner examined how levels of antisemitism fluctuated during wartime, and his findings are not what you might think. Mass Observation terminated its survey on antisemitism in Britain during the war because Tom Harrisson assumed that the “present conflict points away” from such attitudes. But that wasn’t what happened. An observer in London in 1939 referred to an “almost universal antisemitic feeling”. And at the end of the war, Hampstead residents got up a petition in 1945 aimed at removing “aliens” (i.e. Jews) from their area. (With so much recent interest in stories of the Kindertransport, it’s easy to overlook that the UK was not at all keen on taking in refugees but maintained tight restrictions.) Kushner describes how “Jewish financiers” were attacked from both left and right. The fascist BUF linked “international Jewish power” to “Jewish communism”. Amongst supporters of the Communist Party there was still antisemitism directed at “rich Jews”.

Across the political spectrum although many were ambivalent, there were plenty saying outright that Jews deserved their treatment. For the right, Jews were either too rich and powerful or dangerous agents of communism. For the left, they were rich oppressors. For the liberal centre, they were responsible for antisemitism for refusing to integrate fully and could solve the problem if they gave up being Jewish. These were already well-worn themes that some found useful guides for reacting to news and events.

“To many, Jews were not victims but oppressors and thus they could not suffer from Nazi attacks. At worst only working-class Jews would be victims. Thus some left-wing anti-war organs cast doubt on the accuracy of the atrocity reports…the reports were just propaganda justifying an imperialist war.”

Kushner’s conclusion from his survey of what he terms the “defence literature”, a good label for my inherited collection, was that much of it was apologetic in tone, tried to be fair to two sides and in effect boiled down to what he calls sugar-coated antisemitism. His one exception was Louis Golding’s book. Kushner is right that The Jewish Problem is a more bracing read.

For a start, the first chapter is called The Gentile Problem, and Golding writes that the whole book should really have had that title as it’s more accurate. He is the one author who states from the outset, simply and without reservations, that antisemitism is never the fault or responsibility of Jews themselves and there’s nothing they can do to solve what’s been called the “Jewish Problem”.

“There is no contribution the Jews can make which is not sooner or later pronounced an aggravation.”

Maurice Samuel made a similar point in The Great Hatred, that “the internal structure of contemporaneous Jewish life has no bearing on the function of anti-Semitism”. Samuel’s analysis was as much psychological as political, as he thought it was urgent for people to understand the psychic pull of totalitarian antisemitism and how deranged – and dangerous for everyone – it was. Like Golding, he argued that instead of trying to find rational causes which might have worked for older forms of anti-Jewish prejudice, we needed to develop explanations for why antisemites were drawn to the utterly irrational modern version with its unhinged paranoia and absurd conspiracies… “the inclination and need to believe hobgoblin stories cannot be treated by refuting the contents of the stories”. Samuel reckoned antisemites included people giving up the moral and intellectual effort of grappling with a complex world. It was easier to surrender to a system of belief in an evil controlling force, especially if you already disliked Jews or rather whoever you imagined Jews to be.

Remembering some of my own experiences of English antisemitism in its politer forms, I’m not sure I could apply the distinctions these authors mostly drew between (1) anti-Jewishness and (2) antisemitism. Things said directly to me by those of an older generation who lived through WW2 overlapped, for instance: “There are some good Jews” – (surely a 1) but also “Israel is the cause of all the trouble in the world” (surely a 2). “Hitler didn’t do a good enough job”, a kid in my sister’s class at our primary school told her, and some children now are still using and hearing the same line, so its transmission has apparently continued. While there’s vast evidence of the systematic spread of antisemitism online, much as these books described an organised, systematic spread of Nazi hate, there’s also somebody scribbling “kill Jews” graffiti in my neighbourhood, and that’s not an isolated recent example. And Kushner’s cutting point still applies, that a lot of so-called defensive argument shifts the blame for antisemitism from its perpetrators to its targets.

I’m not too pessimistic. There’s far more awareness now and more people concerned to challenge all kinds of racism and beliefs in imaginary conspiracies. I hope there are enough of us.

And now, do you want to try an exam question from 80 years ago? It’s a good one for getting a sense of its original candidates.

Proficiency in English, January 1944. Question 2. Rewrite the following in good English, keeping as near to the sense as possible: –

“I am in England now since the fall of France, and in London already since one year and six months. I know full well that I even speak very badly English, what to say of writing. I have not learnt the English in my school, and because I am talking all the days with my fellow natives I was not improving here, and indeed I have been ashamed to have written to you in such bad English, but there is no helping it because I ought to ask you some things very important. I shall be hoping that I might be receiving a reply of you.”

Good luck with the question, and welcome, or welcome back to Elephantdentistry.

A pendant for carrying round an amulet needed to be hollow, like this:

A pendant for carrying round an amulet needed to be hollow, like this: